Eastern Front (World War II) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

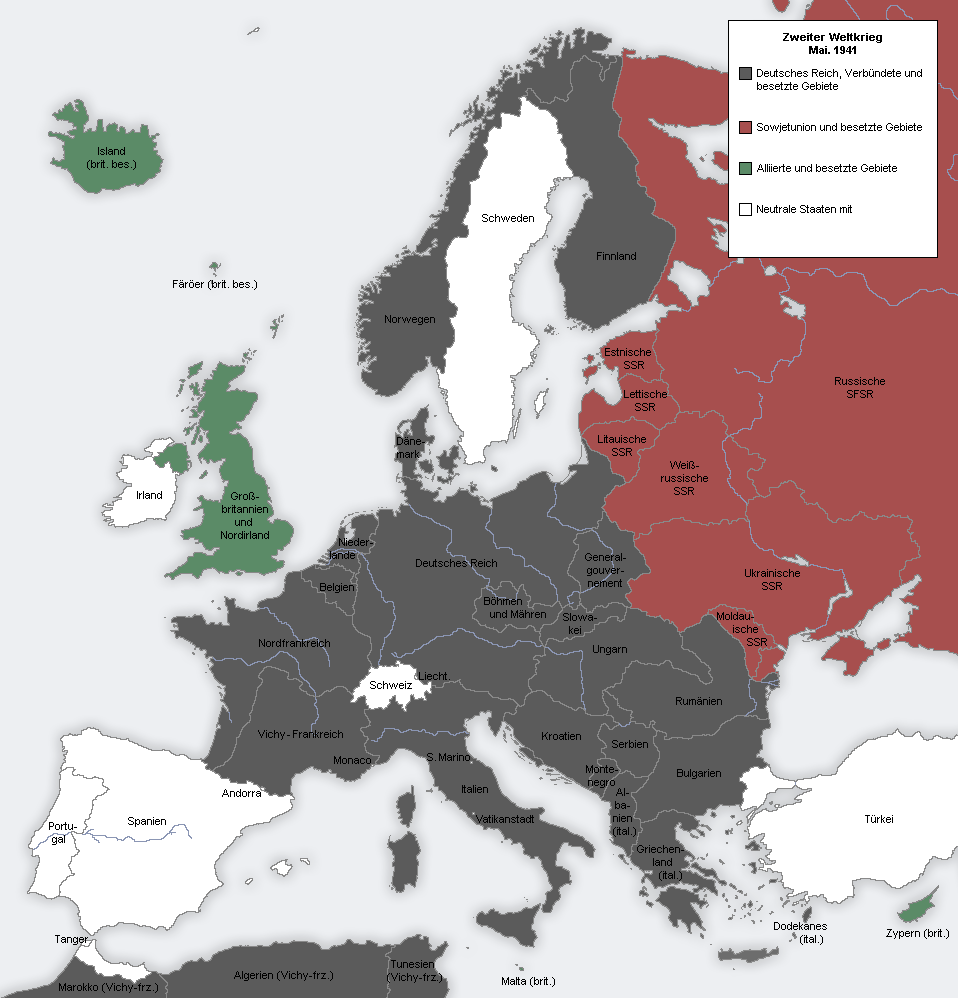

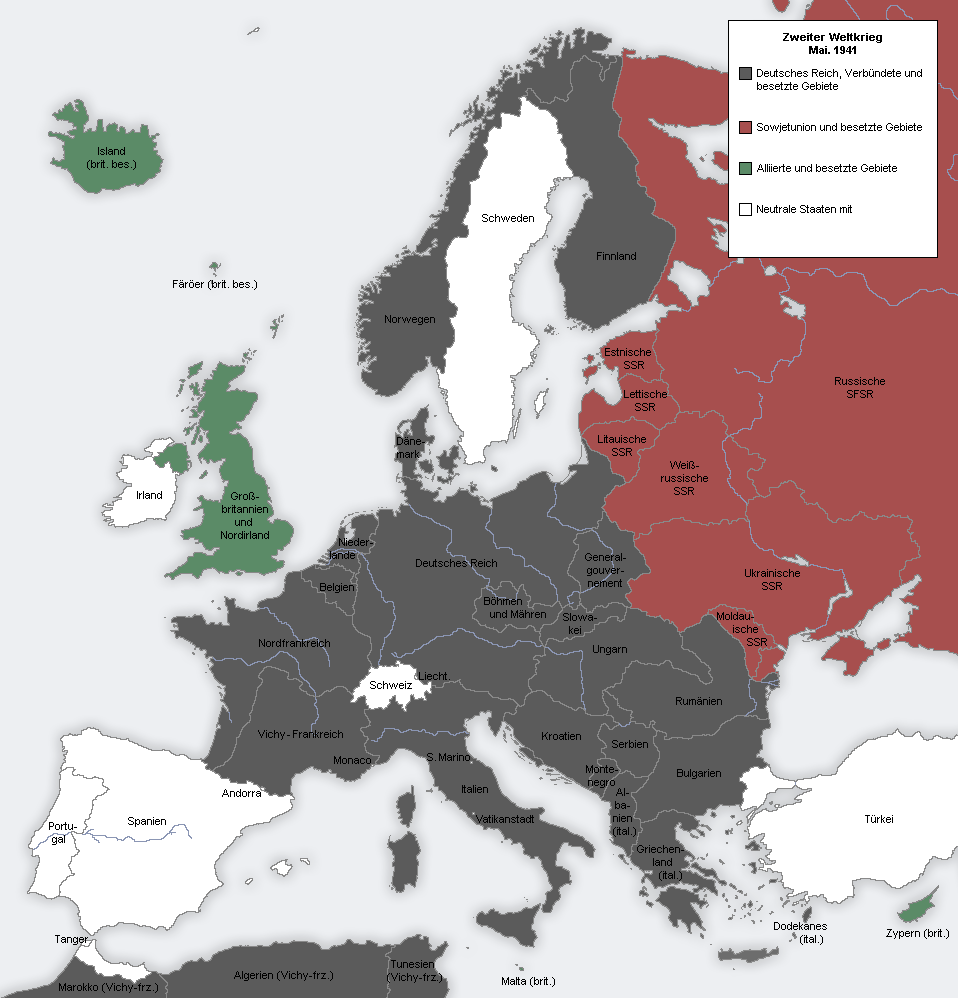

The Eastern Front of

Throughout the 1930s the Soviet Union underwent massive

Throughout the 1930s the Soviet Union underwent massive

The war was fought between

The war was fought between  By July 1943, the Wehrmacht numbered 6,815,000 troops. Of these, 3,900,000 were deployed in eastern Europe, 180,000 in Finland, 315,000 in Norway, 110,000 in Denmark, 1,370,000 in western Europe, 330,000 in Italy, and 610,000 in the Balkans. According to a presentation by Alfred Jodl, the Wehrmacht was up to 7,849,000 personnel in April 1944. 3,878,000 were deployed in eastern Europe, 311,000 in Norway/Denmark, 1,873,000 in western Europe, 961,000 in Italy, and 826,000 in the Balkans. About 15–20% of total German strength were foreign troops (from allied countries or conquered territories). The German high water mark was just before the

By July 1943, the Wehrmacht numbered 6,815,000 troops. Of these, 3,900,000 were deployed in eastern Europe, 180,000 in Finland, 315,000 in Norway, 110,000 in Denmark, 1,370,000 in western Europe, 330,000 in Italy, and 610,000 in the Balkans. According to a presentation by Alfred Jodl, the Wehrmacht was up to 7,849,000 personnel in April 1944. 3,878,000 were deployed in eastern Europe, 311,000 in Norway/Denmark, 1,873,000 in western Europe, 961,000 in Italy, and 826,000 in the Balkans. About 15–20% of total German strength were foreign troops (from allied countries or conquered territories). The German high water mark was just before the  Germany had been assembling very large numbers of troops in eastern Poland and making repeated

Germany had been assembling very large numbers of troops in eastern Poland and making repeated

Germany's economic, scientific, research and industrial capabilities were among the most technically advanced in the world at the time. However, access to (and control of) the

Germany's economic, scientific, research and industrial capabilities were among the most technically advanced in the world at the time. However, access to (and control of) the

an

Part 2

. Counting deaths and turnover, about 15 million men and women were forced labourers at one point during the war. For example, 1.5 million French soldiers were kept in POW camps in Germany as hostages and forced workers and, in 1943, 600,000 French civilians were forced to move to Germany to work in war plants. The defeat of Germany in 1945 freed approximately 11 million foreigners (categorised as "displaced persons"), most of whom were forced labourers and POWs. In wartime, the German forces had brought into the Reich 6.5 million civilians in addition to Soviet POWs for

While German historians do not apply any specific periodisation to the conduct of operations on the Eastern Front, all Soviet and Russian historians divide the war against Germany and its allies into three periods, which are further subdivided into eight major campaigns of the Theatre of war:

* First period (russian: Первый период Великой Отечественной войны) (22 June 1941 – 18 November 1942)

# Summer–Autumn Campaign of 1941 (russian: Летне-осенняя кампания 1941 г.) (22 June – 4 December 1941)

# Winter Campaign of 1941–42 (russian: Зимняя кампания 1941/42 г.) (5 December 1941 – 30 April 1942)

# Summer–Autumn Campaign of 1942 (russian: Летне-осенняя кампания 1942 г.) (1 May – 18 November 1942)

* Second period (russian: Второй период Великой Отечественной войны) (19 November 1942 – 31 December 1943)

# Winter Campaign of 1942–43 (russian: Зимняя кампания 1942–1943 гг.) (19 November 1942 – 3 March 1943)

# Summer–Autumn Campaign of 1943 (russian: Летне-осенняя кампания 1943 г.) (1 July – 31 December 1943)

* Third period (russian: Третий период Великой Отечественной войны) (1 January 1944 – 9 May 1945)

# Winter–Spring Campaign (russian: Зимне-весенняя кампания 1944 г.) (1 January – 31 May 1944)

# Summer–Autumn Campaign of 1944 (russian: Летне-осенняя кампания 1944 г.) (1 June – 31 December 1944)

# Campaign in Europe during 1945 (russian: Кампания в Европе 1945 г.) (1 January – 8 May 1945)

While German historians do not apply any specific periodisation to the conduct of operations on the Eastern Front, all Soviet and Russian historians divide the war against Germany and its allies into three periods, which are further subdivided into eight major campaigns of the Theatre of war:

* First period (russian: Первый период Великой Отечественной войны) (22 June 1941 – 18 November 1942)

# Summer–Autumn Campaign of 1941 (russian: Летне-осенняя кампания 1941 г.) (22 June – 4 December 1941)

# Winter Campaign of 1941–42 (russian: Зимняя кампания 1941/42 г.) (5 December 1941 – 30 April 1942)

# Summer–Autumn Campaign of 1942 (russian: Летне-осенняя кампания 1942 г.) (1 May – 18 November 1942)

* Second period (russian: Второй период Великой Отечественной войны) (19 November 1942 – 31 December 1943)

# Winter Campaign of 1942–43 (russian: Зимняя кампания 1942–1943 гг.) (19 November 1942 – 3 March 1943)

# Summer–Autumn Campaign of 1943 (russian: Летне-осенняя кампания 1943 г.) (1 July – 31 December 1943)

* Third period (russian: Третий период Великой Отечественной войны) (1 January 1944 – 9 May 1945)

# Winter–Spring Campaign (russian: Зимне-весенняя кампания 1944 г.) (1 January – 31 May 1944)

# Summer–Autumn Campaign of 1944 (russian: Летне-осенняя кампания 1944 г.) (1 June – 31 December 1944)

# Campaign in Europe during 1945 (russian: Кампания в Европе 1945 г.) (1 January – 8 May 1945)

As the

As the

Hitler then decided to resume the advance on Moscow, re-designating the panzer groups as panzer armies for the occasion.

Hitler then decided to resume the advance on Moscow, re-designating the panzer groups as panzer armies for the occasion.

The Soviet counter-offensive during the Battle of Moscow had removed the immediate German threat to the city. According to

The Soviet counter-offensive during the Battle of Moscow had removed the immediate German threat to the city. According to  The main blow was to be delivered by a

The main blow was to be delivered by a

Although plans were made to attack Moscow again, on 28 June 1942, the offensive re-opened in a different direction. Army Group South took the initiative, anchoring the front with the Battle of Voronezh and then following the

Although plans were made to attack Moscow again, on 28 June 1942, the offensive re-opened in a different direction. Army Group South took the initiative, anchoring the front with the Battle of Voronezh and then following the

While the German 6th and 4th Panzer Armies had been fighting their way into Stalingrad, Soviet armies had congregated on either side of the city, specifically into the Don

While the German 6th and 4th Panzer Armies had been fighting their way into Stalingrad, Soviet armies had congregated on either side of the city, specifically into the Don

The Germans rushed to transfer troops to the Soviet Union in a desperate attempt to relieve Stalingrad, but the offensive could not get going until 12 December, by which time the 6th Army in Stalingrad was starving and too weak to break out towards it.

The Germans rushed to transfer troops to the Soviet Union in a desperate attempt to relieve Stalingrad, but the offensive could not get going until 12 December, by which time the 6th Army in Stalingrad was starving and too weak to break out towards it.

After the failure of the attempt to capture Stalingrad, Hitler had delegated planning authority for the upcoming campaign season to the German Army High Command and reinstated

After the failure of the attempt to capture Stalingrad, Hitler had delegated planning authority for the upcoming campaign season to the German Army High Command and reinstated  In the north, the entire German 9th Army had been redeployed from the Rzhev salient into the Orel salient and was to advance from Maloarkhangelsk to Kursk. But its forces could not even get past the first objective at

In the north, the entire German 9th Army had been redeployed from the Rzhev salient into the Orel salient and was to advance from Maloarkhangelsk to Kursk. But its forces could not even get past the first objective at  After the war, the battle near Prochorovka was idealised by Soviet

After the war, the battle near Prochorovka was idealised by Soviet

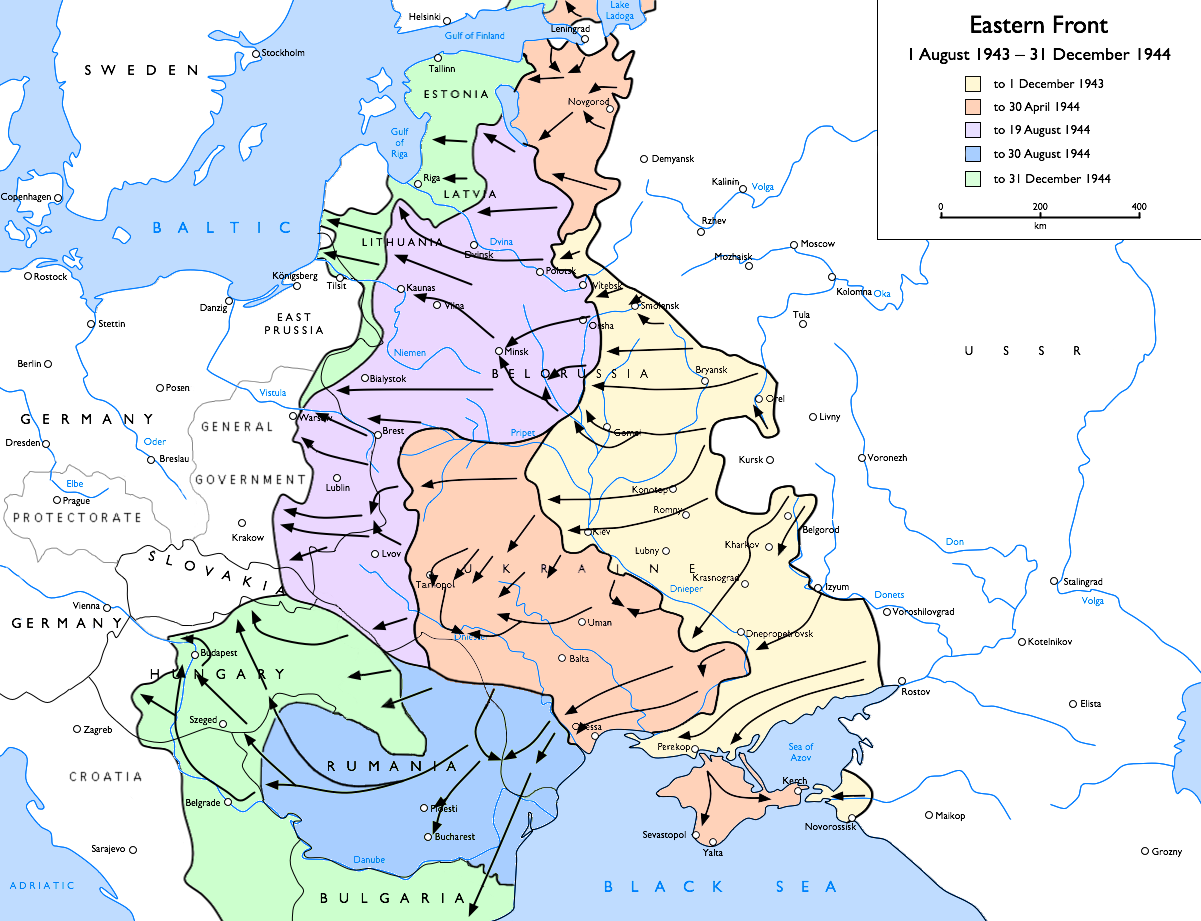

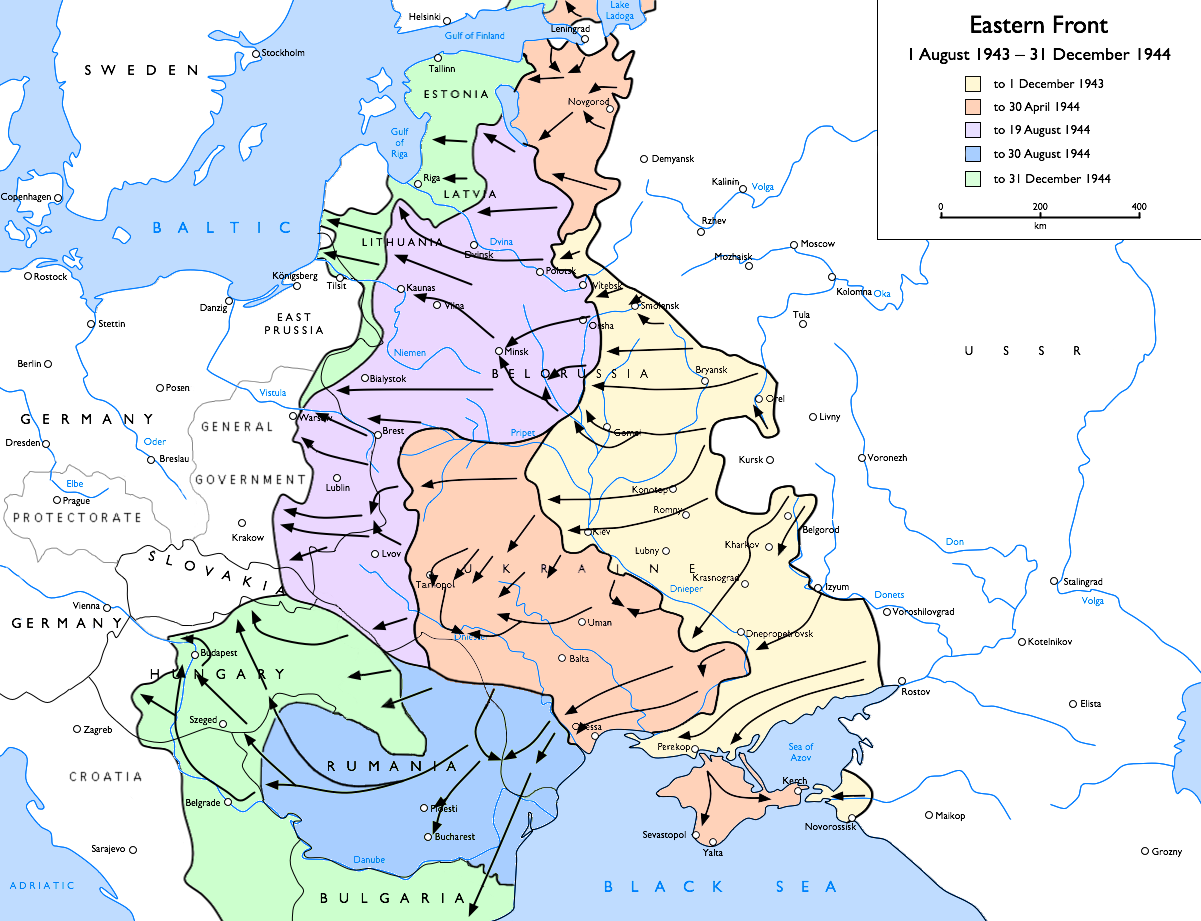

The Soviet multi-stage summer offensive started with the advance into the Orel salient. The diversion of the well-equipped ''Großdeutschland Division'' from Belgorod to Karachev could not counteract it, and the Wehrmacht began a withdrawal from Orel (retaken by the Red Army on 5 August 1943), falling back to the Hagen line in front of

The Soviet multi-stage summer offensive started with the advance into the Orel salient. The diversion of the well-equipped ''Großdeutschland Division'' from Belgorod to Karachev could not counteract it, and the Wehrmacht began a withdrawal from Orel (retaken by the Red Army on 5 August 1943), falling back to the Hagen line in front of  One final move in the south completed the 1943–44 campaigning season, which had wrapped up a Soviet advance of over . In March, 20 German divisions of ''

One final move in the south completed the 1943–44 campaigning season, which had wrapped up a Soviet advance of over . In March, 20 German divisions of ''

''Wehrmacht'' planners were convinced that the Red Army would attack again in the south, where the front was from

''Wehrmacht'' planners were convinced that the Red Army would attack again in the south, where the front was from  The rapid progress of Operation Bagration threatened to cut off and isolate the German units of

The rapid progress of Operation Bagration threatened to cut off and isolate the German units of

The Soviet Union finally entered

The Soviet Union finally entered  A limited counter-attack (codenamed

A limited counter-attack (codenamed

The Soviet offensive had two objectives. Because of Stalin's suspicions about the intentions of the

The Soviet offensive had two objectives. Because of Stalin's suspicions about the intentions of the  On 29 and 30 April, as the Soviet forces fought their way into the centre of Berlin, Adolf Hitler married

On 29 and 30 April, as the Soviet forces fought their way into the centre of Berlin, Adolf Hitler married

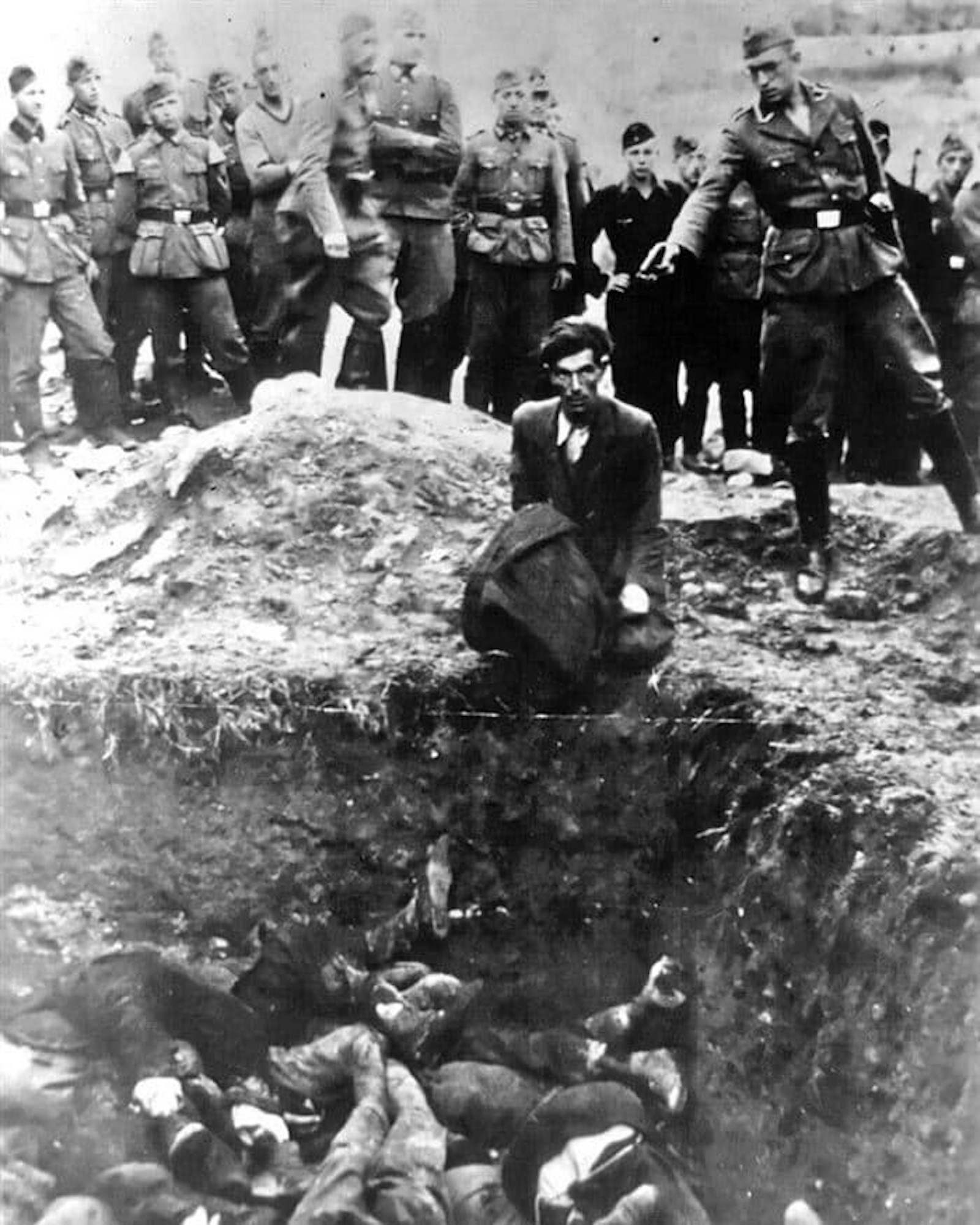

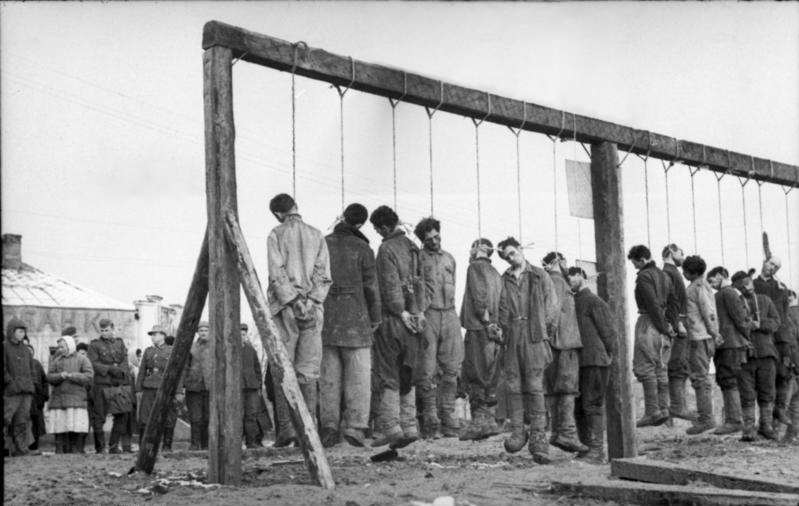

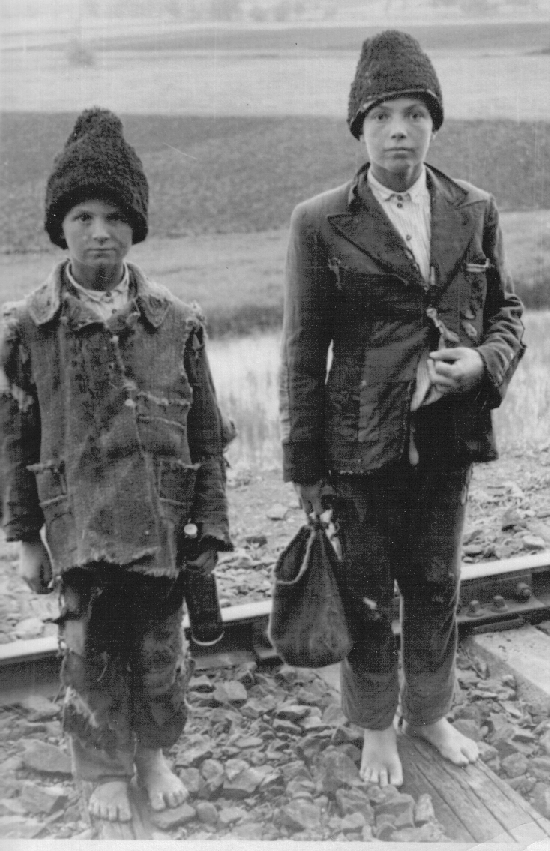

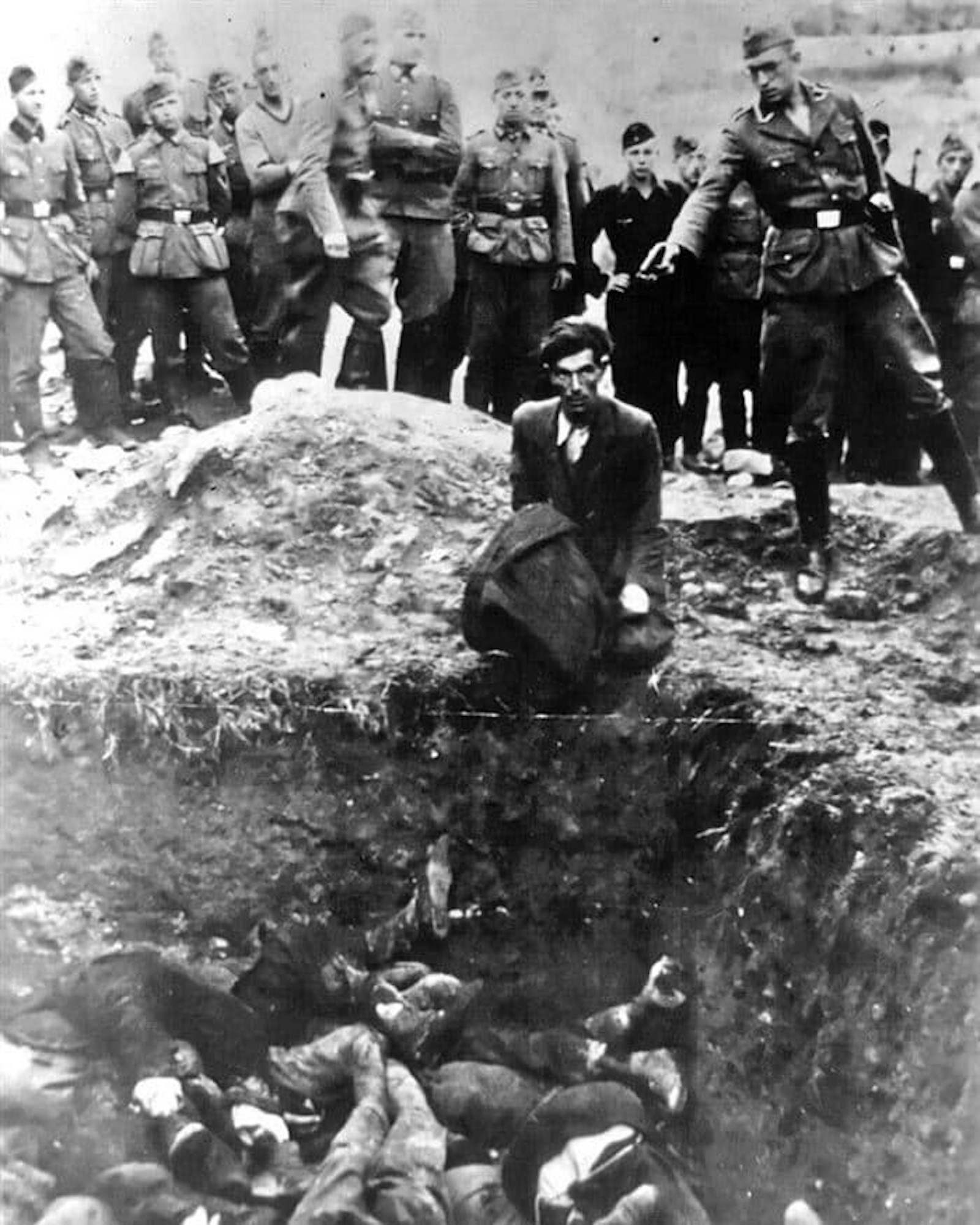

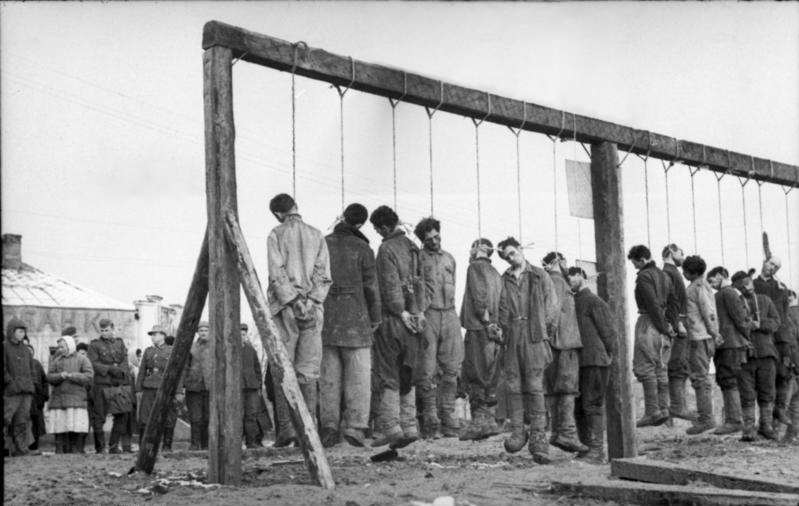

The war inflicted huge losses and suffering upon the civilian populations of the affected countries. Behind the front lines, atrocities against civilians in German-occupied areas were routine, including those carried out as part of the Holocaust. German and German-allied forces treated civilian populations with exceptional brutality, massacring whole village populations and routinely killing civilian hostages (see

The war inflicted huge losses and suffering upon the civilian populations of the affected countries. Behind the front lines, atrocities against civilians in German-occupied areas were routine, including those carried out as part of the Holocaust. German and German-allied forces treated civilian populations with exceptional brutality, massacring whole village populations and routinely killing civilian hostages (see

The enormous territorial gains of 1941 presented Germany with vast areas to pacify and administer. For the majority of people of the Soviet Union, the Nazi invasion was viewed as a brutal act of unprovoked aggression. While it is important to note that not all parts of Soviet society viewed the German advance in this way, the majority of the Soviet population viewed German forces as occupiers. In areas such as Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania (which had been annexed by the Soviet Union in 1940) the ''Wehrmacht'' was tolerated by a relatively more significant part of the native population.

The enormous territorial gains of 1941 presented Germany with vast areas to pacify and administer. For the majority of people of the Soviet Union, the Nazi invasion was viewed as a brutal act of unprovoked aggression. While it is important to note that not all parts of Soviet society viewed the German advance in this way, the majority of the Soviet population viewed German forces as occupiers. In areas such as Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania (which had been annexed by the Soviet Union in 1940) the ''Wehrmacht'' was tolerated by a relatively more significant part of the native population.

This was particularly true for the territories of Western Ukraine, recently rejoined to the Soviet Union, where the anti-Polish and anti-Soviet Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists, Ukrainian nationalist underground hoped in vain to establish the "independent state", relying on German armed force. However, Soviet society as a whole was hostile to the invading Nazis from the very start. The nascent national liberation movements among Ukrainians and Cossacks, and others were viewed by Hitler with suspicion; some, especially those from the Baltic States, were co-opted into the Axis armies and others brutally suppressed. None of the conquered territories gained any measure of self-rule.

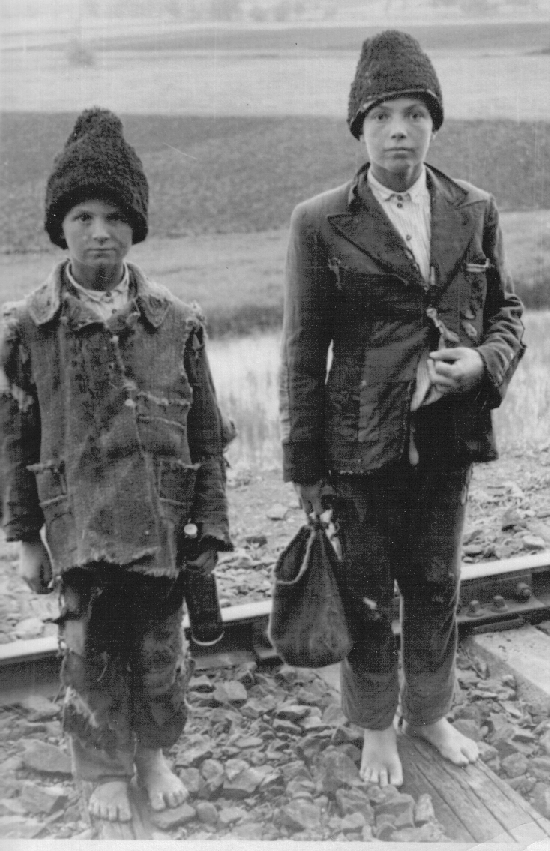

Instead, the Nazism, Nazi ideologues saw the future of the East as one of settlement by German colonists, with the natives killed, expelled, or reduced to slave labour. The cruel and brutally inhumane treatment of Soviet civilians, women, children and elderly, the daily bombings of civilian cities and towns, Nazi pillaging of Soviet villages and hamlets and unprecedented harsh punishment and treatment of civilians in general were some of the primary reasons for Soviet resistance to Nazi Germany's invasion. Indeed, the Soviets viewed Germany's invasion as an act of aggression and an attempt to conquer and enslave the local population.

This was particularly true for the territories of Western Ukraine, recently rejoined to the Soviet Union, where the anti-Polish and anti-Soviet Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists, Ukrainian nationalist underground hoped in vain to establish the "independent state", relying on German armed force. However, Soviet society as a whole was hostile to the invading Nazis from the very start. The nascent national liberation movements among Ukrainians and Cossacks, and others were viewed by Hitler with suspicion; some, especially those from the Baltic States, were co-opted into the Axis armies and others brutally suppressed. None of the conquered territories gained any measure of self-rule.

Instead, the Nazism, Nazi ideologues saw the future of the East as one of settlement by German colonists, with the natives killed, expelled, or reduced to slave labour. The cruel and brutally inhumane treatment of Soviet civilians, women, children and elderly, the daily bombings of civilian cities and towns, Nazi pillaging of Soviet villages and hamlets and unprecedented harsh punishment and treatment of civilians in general were some of the primary reasons for Soviet resistance to Nazi Germany's invasion. Indeed, the Soviets viewed Germany's invasion as an act of aggression and an attempt to conquer and enslave the local population.

Regions closer to the front were managed by military powers of the region, in other areas such as the Baltic states annexed by the USSR in 1940, Reichscommissariats were established. As a rule, the maximum in loot was extracted. In September 1941, Erich Koch was appointed to the Ukrainian Commissariat. His opening speech was clear about German policy: "I am known as a brutal dog ... Our job is to suck from Ukraine all the goods we can get hold of ... I am expecting from you the utmost severity towards the native population."

Atrocities against the Jewish population in the conquered areas began almost immediately, with the dispatch of ''Einsatzgruppen'' (task groups) to round up Jews and shoot them.

The massacres of Jews and other Ethnic minority, ethnic minorities were only a part of the deaths from the Nazi occupation. Many hundreds of thousands of Soviet civilians were executed, and millions more died from starvation as the Germans requisitioned food for their armies and fodder for their draft horses. As they retreated from Ukraine and Belarus in 1943–44, the German occupiers systematically applied a

Regions closer to the front were managed by military powers of the region, in other areas such as the Baltic states annexed by the USSR in 1940, Reichscommissariats were established. As a rule, the maximum in loot was extracted. In September 1941, Erich Koch was appointed to the Ukrainian Commissariat. His opening speech was clear about German policy: "I am known as a brutal dog ... Our job is to suck from Ukraine all the goods we can get hold of ... I am expecting from you the utmost severity towards the native population."

Atrocities against the Jewish population in the conquered areas began almost immediately, with the dispatch of ''Einsatzgruppen'' (task groups) to round up Jews and shoot them.

The massacres of Jews and other Ethnic minority, ethnic minorities were only a part of the deaths from the Nazi occupation. Many hundreds of thousands of Soviet civilians were executed, and millions more died from starvation as the Germans requisitioned food for their armies and fodder for their draft horses. As they retreated from Ukraine and Belarus in 1943–44, the German occupiers systematically applied a  The Nazi ideology and the maltreatment of the local population and Soviet POWs encouraged partisans fighting behind the front; it motivated even anti-communists or non-Russian nationalists to ally with the Soviets and greatly delayed the formation of German-allied divisions consisting of Soviet POWs (see Ostlegionen). These results and missed opportunities contributed to the defeat of the ''Wehrmacht''.

Vadim Erlikman has detailed Soviet losses totalling 26.5 million war related deaths. Military losses of 10.6 million include six million killed or missing in action and 3.6 million POW dead, plus 400,000 paramilitary and Soviet partisans, Soviet partisan losses. Civilian deaths totalled 15.9 million, which included 1.5 million from military actions; 7.1 million victims of Nazi genocide and reprisals; 1.8 million deported to Germany for forced labour; and 5.5 million famine and disease deaths. Additional famine deaths, which totalled one million during 1946–47, are not included here. These losses are for the entire territory of the USSR including territories annexed in 1939–40.

The Nazi ideology and the maltreatment of the local population and Soviet POWs encouraged partisans fighting behind the front; it motivated even anti-communists or non-Russian nationalists to ally with the Soviets and greatly delayed the formation of German-allied divisions consisting of Soviet POWs (see Ostlegionen). These results and missed opportunities contributed to the defeat of the ''Wehrmacht''.

Vadim Erlikman has detailed Soviet losses totalling 26.5 million war related deaths. Military losses of 10.6 million include six million killed or missing in action and 3.6 million POW dead, plus 400,000 paramilitary and Soviet partisans, Soviet partisan losses. Civilian deaths totalled 15.9 million, which included 1.5 million from military actions; 7.1 million victims of Nazi genocide and reprisals; 1.8 million deported to Germany for forced labour; and 5.5 million famine and disease deaths. Additional famine deaths, which totalled one million during 1946–47, are not included here. These losses are for the entire territory of the USSR including territories annexed in 1939–40.

Sixty percent of Soviet POWs died during the war. By its end, large numbers of Soviet POWs, forced labourers and Nazi collaborators (including those who were Operation Keelhaul, forcefully repatriated by the

Sixty percent of Soviet POWs died during the war. By its end, large numbers of Soviet POWs, forced labourers and Nazi collaborators (including those who were Operation Keelhaul, forcefully repatriated by the

The fighting involved millions of Axis and Soviet troops along the broadest land front in military history. It was by far the deadliest single theatre of the European portion of World War II with up to 8.7 to 10 million military deaths on the Soviet side (although, depending on the criteria used, casualties in the Far East theatre may have been similar in number). Axis military deaths were 5 million of which around 4,000,000 were German deaths.

Included in this figure of German losses is the majority of the 2 million German military personnel listed as missing or unaccounted for after the war. Rüdiger Overmans states that it seems entirely plausible, while not provable, that one half of these men were killed in action and the other half died in Soviet custody. Official OKW Casualty Figures list 65% of Heer killed/missing/captured as being lost on the Eastern Front from 1 September 1939, to 1 January 1945 (four months and a week before the conclusion of the war), with front not specified for losses of the Kriegsmarine and Luftwaffe.

Estimated civilian deaths range from about 14 to 17 million. Over 11.4 million Soviet civilians within pre-1939 Soviet borders were killed, and another estimated 3.5 million civilians were killed in the annexed territories. The Nazis exterminated one to two million Soviet Jews (including the annexed territories) as part of the Holocaust.Martin Gilbert. ''Atlas of the Holocaust'' 1988 Soviet and Russian historiography often uses the term "irretrievable casualties". According to the Narkomat of Defence order (No. 023, 4 February 1944), the irretrievable casualties include killed, missing, those who died due to war-time or subsequent wounds, maladies and chilblains and those who were captured.

The huge death toll was attributed to several factors, including brutal mistreatment of POWs and captured partisans, the large deficiency of food and medical supplies in Soviet territories, and atrocities committed mostly by the Germans against the civilian population. The multiple battles and the use of

The fighting involved millions of Axis and Soviet troops along the broadest land front in military history. It was by far the deadliest single theatre of the European portion of World War II with up to 8.7 to 10 million military deaths on the Soviet side (although, depending on the criteria used, casualties in the Far East theatre may have been similar in number). Axis military deaths were 5 million of which around 4,000,000 were German deaths.

Included in this figure of German losses is the majority of the 2 million German military personnel listed as missing or unaccounted for after the war. Rüdiger Overmans states that it seems entirely plausible, while not provable, that one half of these men were killed in action and the other half died in Soviet custody. Official OKW Casualty Figures list 65% of Heer killed/missing/captured as being lost on the Eastern Front from 1 September 1939, to 1 January 1945 (four months and a week before the conclusion of the war), with front not specified for losses of the Kriegsmarine and Luftwaffe.

Estimated civilian deaths range from about 14 to 17 million. Over 11.4 million Soviet civilians within pre-1939 Soviet borders were killed, and another estimated 3.5 million civilians were killed in the annexed territories. The Nazis exterminated one to two million Soviet Jews (including the annexed territories) as part of the Holocaust.Martin Gilbert. ''Atlas of the Holocaust'' 1988 Soviet and Russian historiography often uses the term "irretrievable casualties". According to the Narkomat of Defence order (No. 023, 4 February 1944), the irretrievable casualties include killed, missing, those who died due to war-time or subsequent wounds, maladies and chilblains and those who were captured.

The huge death toll was attributed to several factors, including brutal mistreatment of POWs and captured partisans, the large deficiency of food and medical supplies in Soviet territories, and atrocities committed mostly by the Germans against the civilian population. The multiple battles and the use of  Based on Soviet sources Krivosheev put German losses on the Eastern Front from 1941 to 1945 at 6,923,700 men: including killed in action, died of wounds or disease and reported missing and presumed dead4,137,100, taken prisoner 2,571,600 and 215,000 dead among Collaboration in the German-occupied Soviet Union, Soviet volunteers in the Wehrmacht. Deaths of POW were 450,600 including 356,700 in NKVD camps and 93,900 in transit.

According to a report prepared by the General Staff of the Army issued in December 1944, materiel losses in the East from the period of 22 June 1941 until November 1944 stood at 33,324 armoured vehicles of all types (tanks, assault guns, tank destroyers, self-propelled guns and others). Paul Winter, ''Defeating Hitler'', states "these figures are undoubtedly too low". According to Soviet claims, the Germans lost 42,700 tanks, tank destroyers, self-propelled guns and assault guns on the Eastern front. Overall, Germany produced 3,024 reconnaissance vehicles, 2,450 other armoured vehicles, 21,880 armoured personnel carriers, 36,703 semi-tracked tractors and 87,329 semi-tracked trucks, estimated 2/3 were lost on the Eastern Front.

The Soviets lost 96,500 tanks, tank destroyers, self-propelled guns and assault guns, as well as 37,600 other armoured vehicles (such as armoured cars and semi-tracked trucks) for a total of 134,100 armoured vehicles lost.

The Soviets also lost 102,600 aircraft (combat and non-combat causes), including 46,100 in combat. According to Soviet claims, the Germans lost 75,700 aircraft on the Eastern front.Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Encyclopedia of Casualty and Other Figures, 1492–2015, 4th ed. Micheal Clodfelter

Based on Soviet sources Krivosheev put German losses on the Eastern Front from 1941 to 1945 at 6,923,700 men: including killed in action, died of wounds or disease and reported missing and presumed dead4,137,100, taken prisoner 2,571,600 and 215,000 dead among Collaboration in the German-occupied Soviet Union, Soviet volunteers in the Wehrmacht. Deaths of POW were 450,600 including 356,700 in NKVD camps and 93,900 in transit.

According to a report prepared by the General Staff of the Army issued in December 1944, materiel losses in the East from the period of 22 June 1941 until November 1944 stood at 33,324 armoured vehicles of all types (tanks, assault guns, tank destroyers, self-propelled guns and others). Paul Winter, ''Defeating Hitler'', states "these figures are undoubtedly too low". According to Soviet claims, the Germans lost 42,700 tanks, tank destroyers, self-propelled guns and assault guns on the Eastern front. Overall, Germany produced 3,024 reconnaissance vehicles, 2,450 other armoured vehicles, 21,880 armoured personnel carriers, 36,703 semi-tracked tractors and 87,329 semi-tracked trucks, estimated 2/3 were lost on the Eastern Front.

The Soviets lost 96,500 tanks, tank destroyers, self-propelled guns and assault guns, as well as 37,600 other armoured vehicles (such as armoured cars and semi-tracked trucks) for a total of 134,100 armoured vehicles lost.

The Soviets also lost 102,600 aircraft (combat and non-combat causes), including 46,100 in combat. According to Soviet claims, the Germans lost 75,700 aircraft on the Eastern front.Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Encyclopedia of Casualty and Other Figures, 1492–2015, 4th ed. Micheal Clodfelter

, 9780786474707. P. 449 When the Axis countries of Central Europe were occupied by the Soviets, they changed sides and declared war on Germany (see Allied Commissions).

Some Soviet citizens would side with the Germans and join

When the Axis countries of Central Europe were occupied by the Soviets, they changed sides and declared war on Germany (see Allied Commissions).

Some Soviet citizens would side with the Germans and join

The Eastern Front: Barbarossa, Stalingrad, Kursk and Berlin (Campaigns of World War II)

'. London: Amber Books Ltd., 2001. . * Antony Beevor, Beevor, Antony. ''Stalingrad: The Fateful Siege: 1942–1943''. New York: Penguin Books, 1998. . * Beevor, Antony. ''Berlin: The Downfall 1945''. New York: Penguin Books, 2002, * Dick, C. J. ''From Defeat to Victory: The Eastern Front, Summer 1944'' volume 2 of "Decisive and Indecisive Military Operations" (University Press of Kansas, 2016

online review

uy * Erickson, John. ''The Road to Stalingrad. Stalin's War against Germany''. New York: Orion Publishing Group, 2007. . * Erickson, John. ''The Road to Berlin. Stalin's War against Germany''. New York: Orion Publishing Group, Ltd., 2007. . * Erickson, John, and David Dilks. ''Barbarossa, the Axis and the Allies''. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1995. . * Glantz, David,

The Soviet‐German War 1941–45

Myths and Realities: A Survey Essay''. * Heinz Guderian, Guderian, Heinz. ''Panzer Leader (book), Panzer Leader'', Da Capo Press Reissue edition. New York: Da Capo Press, 2001. . * Max Hastings, Hastings, Max. ''Armageddon: The Battle for Germany, 1944–1945''. Vintage Books USA, 2005. * * International Military Tribunal at Nurnberg, Germany

''Nazi Conspiracy and Aggression, Supplement A''

USGPO, 1947. * * Basil Liddell Hart, Liddell Hart, B.H. ''History of the Second World War''. United States of America: Da Capo Press, 1999. . * Bengt Beckman. ''Svenska Kryptobedrifter''

Lubbeck, William

and David B. Hurt.

At Leningrad's Gates: The Story of a Soldier with Army Group North

', Philadelphia: Casemate, 2006. . * Evan Mawdsley, Mawdsley, Evan ''Thunder in the East: the Nazi–Soviet War, 1941–1945''. London 2005. . * . * Müller, Rolf-Dieter and Gerd R. Ueberschär.

Hitler's War in the East 1941−1945, Hitler's War in the East, 1941–1945

: A Critical Assessment]''. Berghahn Books, 1997. . * Richard Overy, Overy, Richard. ''Russia's War: A History of the Soviet Effort: 1941–1945'', New Edition. New York: Penguin Books Ltd., 1998. . * Schofield, Carey, ''ed''. ''Russian at War, 1941–1945''. Text by Georgii Drozdov and Evgenii Ryabko, [with] introd. by Vladimir Karpov [and] pref. by Harrison E. Salisbury, ed. by Carey Schofield. New York: Vendome Press, 1987. 256 p., copiously ill. with b&2 photos and occasional maps. ''N.B''.: This is mostly a photo-history, with connecting texts. * Seaton, Albert. ''The Russo-German War, 1941–1945'', Reprint edition. Presidio Press, 1993. . * William L. Shirer, Shirer, William L. (1960). ''The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich: A History of Nazi Germany'' New York: Simon & Schuster. * SvD 2010-10-2

Svensk knäckte nazisternas hemliga koder

* F. W. Winterbotham, Winterbotham, F.W. ''The Ultra Secret'', New Edition. Orion Publishing Group Ltd., 2000. . * Ziemke, Earl F. ''Battle For Berlin: End of the Third Reich'', NY:Ballantine Books, London:Macdomald & Co, 1969. * Ziemke, Earl F

''The U.S. Army in the occupation of Germany 1944–1946''

USGPO, 1975

Marking 70 Years to Operation Barbarossa

on the Yad Vashem website

Prof Richard Overy writes a summary about the eastern front for the BBC

World War II: The Eastern Front

by Alan Taylor, ''The Atlantic''

Borodulin Collection. Excellent set of war photos

Pobediteli: Eastern Front flash animation

(photos, video, interviews, memorials. Written from a Russian perspective)

RKKA in World War II

World War II Eastern Front Order Of Battle

Don't forget how the Soviet Union saved the world from Hitler

''The Washington Post'', 8 May 2015.

Images depicting conditions in the camps for Soviet POW

from Yad Vashem

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

was a theatre

Theatre or theater is a collaborative form of performing art that uses live performers, usually actors or actresses, to present the experience of a real or imagined event before a live audience in a specific place, often a stage. The perform ...

of conflict between the European Axis powers

The Axis powers, ; it, Potenze dell'Asse ; ja, 枢軸国 ''Sūjikukoku'', group=nb originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis, was a military coalition that initiated World War II and fought against the Allies. Its principal members were ...

against the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

(USSR), Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populous ...

and other Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

, which encompassed Central Europe

Central Europe is an area of Europe between Western Europe and Eastern Europe, based on a common historical, social and cultural identity. The Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) between Catholicism and Protestantism significantly shaped the area' ...

, Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the Europe, European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural, and socio-economic connotations. The vast majority of the region is covered by Russ ...

, Northeast Europe (Baltics

The Baltic states, et, Balti riigid or the Baltic countries is a geopolitical term, which currently is used to group three countries: Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. All three countries are members of NATO, the European Union, the Eurozone, ...

), and Southeast Europe

Southeast Europe or Southeastern Europe (SEE) is a geographical subregion of Europe, consisting primarily of the Balkans. Sovereign states and territories that are included in the region are Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia (al ...

(Balkans

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

) from 22 June 1941 to 9 May 1945. It was known as the Great Patriotic War

The Eastern Front of World War II was a theatre of conflict between the European Axis powers against the Soviet Union (USSR), Poland and other Allies, which encompassed Central Europe, Eastern Europe, Northeast Europe (Baltics), and Sout ...

in the Soviet Union – and still is in some of its successor states, while almost everywhere else it has been called the ''Eastern Front''. In present-day German and Ukrainian historiography the name German-Soviet War is typically used.

The battles on the Eastern Front of the Second World War constituted the largest military confrontation in history. They were characterised by unprecedented ferocity and brutality, wholesale destruction, mass deportations, and immense loss of life due to combat, starvation, exposure, disease, and massacres. Of the estimated 70–85 million deaths attributed to World War II, around 30 million occurred on the Eastern Front, including 9 million children. The Eastern Front was decisive in determining the outcome in the European theatre of operations

The European theatre of World War II was one of the two main theatres of combat during World War II. It saw heavy fighting across Europe for almost six years, starting with Germany's invasion of Poland on 1 September 1939 and ending with the ...

in World War II, eventually serving as the main reason for the defeat of Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

and the Axis nations.

The two principal belligerent powers were Germany and the Soviet Union, along with their respective allies. Though never sending in ground troops to the Eastern Front, the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

and the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

both provided substantial material aid to the Soviet Union in the form of the Lend-Lease

Lend-Lease, formally the Lend-Lease Act and introduced as An Act to Promote the Defense of the United States (), was a policy under which the United States supplied the United Kingdom, the Soviet Union and other Allied nations with food, oil, ...

program along with naval and air support. The joint German–Finnish operations across the northernmost Finnish–Soviet border and in the Murmansk region

Murmansk Oblast (russian: Му́рманская о́бласть, p=ˈmurmənskəjə ˈobləsʲtʲ, r=Murmanskaya oblast, ''Murmanskaya oblast''; Kildin Sami: Мурман е̄ммьне, ''Murman jemm'ne'') is a federal subject (an oblast) of ...

are considered part of the Eastern Front. In addition, the Soviet–Finnish Continuation War

The Continuation War, also known as the Second Soviet-Finnish War, was a conflict fought by Finland and Nazi Germany against the Soviet Union from 1941 to 1944, as part of World War II.; sv, fortsättningskriget; german: Fortsetzungskrieg. A ...

is generally also considered the northern flank of the Eastern Front.

Background

Germany and the Soviet Union remained unsatisfied withthe outcome

''The'' () is a grammatical article in English, denoting persons or things already mentioned, under discussion, implied or otherwise presumed familiar to listeners, readers, or speakers. It is the definite article in English. ''The'' is the ...

of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

(1914–1918). Soviet Russia

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Russian SFSR or RSFSR ( rus, Российская Советская Федеративная Социалистическая Республика, Rossíyskaya Sovétskaya Federatívnaya Soci ...

had lost substantial territory in Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the Europe, European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural, and socio-economic connotations. The vast majority of the region is covered by Russ ...

as a result of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (also known as the Treaty of Brest in Russia) was a separate peace, separate peace treaty signed on 3 March 1918 between Russian SFSR, Russia and the Central Powers (German Empire, Germany, Austria-Hungary, Kingdom of ...

(March 1918), where the Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

s in Petrograd conceded to German demands and ceded control of Poland, Lithuania, Estonia, Latvia, Finland, and other areas, to the Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,german: Mittelmächte; hu, Központi hatalmak; tr, İttifak Devletleri / ; bg, Централни сили, translit=Tsentralni sili was one of the two main coalitions that fought in ...

. Subsequently, when Germany in its turn surrendered to the Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

(November 1918) and these territories became independent states under the terms of the Paris Peace Conference of 1919

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. S ...

at Versailles

The Palace of Versailles ( ; french: Château de Versailles ) is a former royal residence built by King Louis XIV located in Versailles, about west of Paris, France. The palace is owned by the French Republic and since 1995 has been managed, u ...

, Soviet Russia was in the midst of a civil war and the Allies did not recognise the Bolshevik government, so no Soviet Russian representation attended.

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

had declared his intention to invade the Soviet Union on 11 August 1939 to Carl Jacob Burckhardt

Carl Jacob Burckhardt (September 10, 1891 – March 3, 1974) was a Swiss diplomat and historian. His career alternated between periods of academic historical research and diplomatic postings; the most prominent of the latter were League of Na ...

, League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

Commissioner, by saying:

Everything I undertake is directed against the Russians. If the West is too stupid and blind to grasp this, then I shall be compelled to come to an agreement with the Russians, beat the West and then after their defeat turn against the Soviet Union with all my forces. I need theTheUkraine Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inv ...so that they can't starve us out, as happened in the last war.

Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact

The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact was a non-aggression pact between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union that enabled those powers to partition Poland between them. The pact was signed in Moscow on 23 August 1939 by German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ri ...

signed in August 1939 was a non-aggression agreement between Germany and the Soviet Union. It contained a secret protocol

Protocol may refer to:

Sociology and politics

* Protocol (politics), a formal agreement between nation states

* Protocol (diplomacy), the etiquette of diplomacy and affairs of state

* Etiquette, a code of personal behavior

Science and technolog ...

aiming to return Central Europe

Central Europe is an area of Europe between Western Europe and Eastern Europe, based on a common historical, social and cultural identity. The Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) between Catholicism and Protestantism significantly shaped the area' ...

to the pre–World War I ''status quo'' by dividing it between Germany and the Soviet Union. Finland, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania would return to the Soviet control, while Poland and Romania would be divided. The Eastern Front was also made possible by the German–Soviet Border and Commercial Agreement in which the Soviet Union gave Germany the resources necessary to launch military operations in Eastern Europe.

On 1 September 1939 Germany invaded Poland

The invasion of Poland (1 September – 6 October 1939) was a joint attack on the Republic of Poland by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union which marked the beginning of World War II. The German invasion began on 1 September 1939, one week afte ...

, starting World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

. On 17 September, the Soviet Union invaded Eastern Poland

Eastern Poland is a macroregion in Poland comprising the Lublin, Podkarpackie, Podlaskie, Świętokrzyskie, and Warmian-Masurian voivodeships.

The make-up of the distinct macroregion is based not only of geographical criteria, but also econo ...

, and, as a result, Poland was partitioned among Germany, the Soviet Union and Lithuania. Soon after that, the Soviet Union demanded significant territorial concessions from Finland, and after Finland rejected Soviet demands, the Soviet Union attacked Finland on 30 November 1939 in what became known as the Winter War

The Winter War,, sv, Vinterkriget, rus, Зи́мняя война́, r=Zimnyaya voyna. The names Soviet–Finnish War 1939–1940 (russian: link=no, Сове́тско-финская война́ 1939–1940) and Soviet–Finland War 1 ...

– a bitter conflict that resulted in a peace treaty on 13 March 1940, with Finland maintaining its independence but losing its eastern parts in Karelia.

In June 1940 the Soviet Union occupied and illegally annexed the three Baltic states

The Baltic states, et, Balti riigid or the Baltic countries is a geopolitical term, which currently is used to group three countries: Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. All three countries are members of NATO, the European Union, the Eurozone, ...

(Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania). The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact ostensibly provided security to the Soviets in the occupation both of the Baltics and of the north and northeastern regions of Romania (Northern Bukovina

Bukovinagerman: Bukowina or ; hu, Bukovina; pl, Bukowina; ro, Bucovina; uk, Буковина, ; see also other languages. is a historical region, variously described as part of either Central or Eastern Europe (or both).Klaus Peter BergerT ...

and Bessarabia

Bessarabia (; Gagauz: ''Besarabiya''; Romanian: ''Basarabia''; Ukrainian: ''Бессара́бія'') is a historical region in Eastern Europe, bounded by the Dniester river on the east and the Prut river on the west. About two thirds of Be ...

, June–July 1940), although Hitler, in announcing the invasion of the Soviet Union, cited the Soviet annexations of Baltic and Romanian territory as having violated Germany's understanding of the pact. Moscow partitioned the annexed Romanian territory between the Ukrainian

Ukrainian may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to Ukraine

* Something relating to Ukrainians, an East Slavic people from Eastern Europe

* Something relating to demographics of Ukraine in terms of demography and population of Ukraine

* So ...

and Moldavian Soviet republics.

Ideologies

German ideology

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

had argued in his autobiography ''Mein Kampf

(; ''My Struggle'' or ''My Battle'') is a 1925 autobiographical manifesto by Nazi Party leader Adolf Hitler. The work describes the process by which Hitler became antisemitic and outlines his political ideology and future plans for Germ ...

'' (1925) for the necessity of ''Lebensraum

(, ''living space'') is a German concept of settler colonialism, the philosophy and policies of which were common to German politics from the 1890s to the 1940s. First popularized around 1901, '' lso in:' became a geopolitical goal of Imper ...

'' ("living space"): acquiring new territory for Germans in Eastern Europe, in particular Russia. He envisaged settling Germans there, as according to Nazi ideology the Germanic people constituted the "master race

The master race (german: Herrenrasse) is a pseudoscientific concept in Nazi ideology in which the putative " Aryan race" is deemed the pinnacle of human racial hierarchy. Members were referred to as "''Herrenmenschen''" ("master humans").

T ...

", while exterminating or deporting most of the existing inhabitants to Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a part of ...

and using the remainder as slave labour

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

.

Hitler as early as 1917 had referred to the Russians as inferior, believing that the Bolshevik Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolsheviks, Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was ...

had put the Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

in power over the mass of Slavs

Slavs are the largest European ethnolinguistic group. They speak the various Slavic languages, belonging to the larger Balto-Slavic branch of the Indo-European languages. Slavs are geographically distributed throughout northern Eurasia, main ...

, who were, in Hitler's opinion, incapable of ruling themselves and had thus ended up being ruled by Jewish masters.

The Nazi leadership, including Heinrich Himmler

Heinrich Luitpold Himmler (; 7 October 1900 – 23 May 1945) was of the (Protection Squadron; SS), and a leading member of the Nazi Party of Germany. Himmler was one of the most powerful men in Nazi Germany and a main architect of th ...

, saw the war against the Soviet Union as a struggle between the ideologies of Nazism

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Na ...

and Jewish Bolshevism

Jewish Bolshevism, also Judeo–Bolshevism, is an anti-communist and antisemitic canard, which alleges that the Jews were the originators of the Russian Revolution in 1917, and that they held primary power among the Bolsheviks who led the revo ...

, and ensuring territorial expansion for the Germanic ''Übermensch

The (; "Overhuman") is a concept in the philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche. In his 1883 book ''Thus Spoke Zarathustra'' (german: Also sprach Zarathustra), Nietzsche has his character Zarathustra posit the as a goal for humanity to set for itse ...

'' (superhumans), who according to Nazi ideology were the Aryan ''Herrenvolk

The master race (german: Herrenrasse) is a pseudoscientific concept in Nazi ideology in which the putative "Aryan race" is deemed the pinnacle of human racial hierarchy. Members were referred to as "''Herrenmenschen''" ("master humans").

Th ...

'' ("master race"), at the expense of the Slavic ''Untermenschen

''Untermensch'' (, ; plural: ''Untermenschen'') is a Nazi term for non-Aryan "inferior people" who were often referred to as "the masses from the East", that is Jews, Roma, and Slavs (mainly ethnic Poles, Serbs, and later also Russians). The ...

'' (subhumans). Wehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the ''Heer'' (army), the ''Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmacht''" replaced the previous ...

officers told their troops to target people who were described as "Jewish Bolshevik subhumans", the "Mongol hordes", the "Asiatic flood" and the "red beast". The vast majority of German soldiers viewed the war in Nazi terms, seeing the Soviet enemy as sub-human.

Hitler referred to the war in radical terms, calling it a "war of annihilation

A war of annihilation (german: Vernichtungskrieg) or war of extermination is a type of war in which the goal is the complete annihilation of a state, a people or an ethnic minority through genocide or through the destruction of their livelihood. ...

" (''Vernichtungskrieg'') which was both an ideological and racial war. The Nazi vision for the future of Eastern Europe was codified most clearly in the ''Generalplan Ost

The ''Generalplan Ost'' (; en, Master Plan for the East), abbreviated GPO, was the Nazi German government's plan for the genocide and ethnic cleansing on a vast scale, and colonization of Central and Eastern Europe by Germans. It was to be un ...

''. The populations of occupied Central Europe and the Soviet Union were to be partially deported to West Siberia, enslaved and eventually exterminated; the conquered territories were to be colonised by German or "Germanized" settlers. In addition, the Nazis also sought to wipe out the large Jewish population of Central and Eastern Europe

as part of their program aiming to exterminate all European Jews.

After Germany's initial success at the Battle of Kiev in 1941, Hitler saw the Soviet Union as militarily weak and ripe for immediate conquest. In a speech at the Berlin Sportpalast

Berlin Sportpalast (; built 1910, demolished 1973) was a multi-purpose indoor arena located in the Schöneberg section of Berlin, Germany. Depending on the type of event and seating configuration, the Sportpalast could hold up to 14,000 people ...

on 3 October, he announced, "We have only to kick in the door and the whole rotten structure will come crashing down." Thus, Germany expected another short ''Blitzkrieg

Blitzkrieg ( , ; from 'lightning' + 'war') is a word used to describe a surprise attack using a rapid, overwhelming force concentration that may consist of armored and motorized or mechanized infantry formations, together with close air su ...

'' and made no serious preparations for prolonged warfare. However, following the decisive Soviet victory at the Battle of Stalingrad

The Battle of Stalingrad (23 August 19422 February 1943) was a major battle on the Eastern Front of World War II where Nazi Germany and its allies unsuccessfully fought the Soviet Union for control of the city of Stalingrad (later re ...

in 1943 and the resulting dire German military situation, Nazi propaganda began to portray the war as a German defence of Western civilisation against destruction by the vast "Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

hordes" that were pouring into Europe.

Soviet situation

Throughout the 1930s the Soviet Union underwent massive

Throughout the 1930s the Soviet Union underwent massive industrialisation

Industrialisation ( alternatively spelled industrialization) is the period of social and economic change that transforms a human group from an agrarian society into an industrial society. This involves an extensive re-organisation of an econo ...

and economic growth under the leadership of Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secreta ...

. Stalin's central tenet, "Socialism in One Country

Socialism in one country was a Soviet state policy to strengthen socialism within the country rather than socialism globally. Given the defeats of the 1917–1923 European communist revolutions, Joseph Stalin and Nikolai Bukharin encouraged th ...

", manifested itself as a series of nationwide centralised five-year plans from 1929 onwards. This represented an ideological shift in Soviet policy, away from its commitment to the international communist revolution

In political science, a revolution (Latin: ''revolutio'', "a turn around") is a fundamental and relatively sudden change in political power and political organization which occurs when the population revolts against the government, typically due ...

, and eventually leading to the dissolution of the Comintern

The Communist International (Comintern), also known as the Third International, was a Soviet Union, Soviet-controlled international organization founded in 1919 that advocated world communism. The Comintern resolved at its Second Congress to ...

(Third International) organisation in 1943. The Soviet Union started a process of militarisation with the first five-year plan

The first five-year plan (russian: I пятилетний план, ) of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) was a list of economic goals, created by Communist Party General Secretary Joseph Stalin, based on his policy of socialism in ...

that officially began in 1928, although it was only towards the end of the second five-year plan in the mid-1930s that military power became the primary focus of Soviet industrialisation.

In February 1936 the Spanish general election

There are four types of elections in Spain: general elections, elections to the legislatures of the autonomous communities (regional elections), local elections and elections to the European Parliament. General elections and elections to the legi ...

brought many communist leaders into the Popular Front

A popular front is "any coalition of working-class and middle-class parties", including liberal and social democratic ones, "united for the defense of democratic forms" against "a presumed Fascist assault".

More generally, it is "a coalition ...

government in the Second Spanish Republic

The Spanish Republic (), commonly known as the Second Spanish Republic (), was the form of government in Spain from 1931 to 1939. The Republic was proclaimed on 14 April 1931, after the deposition of Alfonso XIII, King Alfonso XIII, and was di ...

, but in a matter of months a right-wing military coup initiated the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebelión, lin ...

of 1936–1939. This conflict soon took on the characteristics of a proxy war

A proxy war is an armed conflict between two states or non-state actors, one or both of which act at the instigation or on behalf of other parties that are not directly involved in the hostilities. In order for a conflict to be considered a pr ...

involving the Soviet Union and left wing volunteers from different countries on the side of the predominantly socialist and communist-led Second Spanish Republic; while Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

, Fascist Italy, and Portugal's Estado Novo took the side of Spanish Nationalists

Francoist Spain ( es, España franquista), or the Francoist dictatorship (), was the period of Spanish history between 1939 and 1975, when Francisco Franco ruled Spain after the Spanish Civil War with the title . After his death in 1975, Spai ...

, the military rebel group led by General Francisco Franco

Francisco Franco Bahamonde (; 4 December 1892 – 20 November 1975) was a Spanish general who led the Nationalist faction (Spanish Civil War), Nationalist forces in overthrowing the Second Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War ...

. It served as a useful testing ground for both the Wehrmacht and the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and, after ...

to experiment with equipment and tactics that they would later employ on a wider scale in the Second World War.

Nazi Germany, which was an anti-communist

Anti-communism is Political movement, political and Ideology, ideological opposition to communism. Organized anti-communism developed after the 1917 October Revolution in the Russian Empire, and it reached global dimensions during the Cold War, w ...

régime, formalised its ideological position on 25 November 1936 by signing the Anti-Comintern Pact

The Anti-Comintern Pact, officially the Agreement against the Communist International was an anti-Communist pact concluded between Nazi Germany and the Empire of Japan on 25 November 1936 and was directed against the Communist International (Com ...

with Imperial Japan

The also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was a historical nation-state and great power that existed from the Meiji Restoration in 1868 until the enactment of the post-World War II 1947 constitution and subsequent forma ...

. Fascist Italy joined the Pact a year later. The Soviet Union negotiated treaties of mutual assistance with France and with Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

with the aim of containing Germany's expansion. The German ''Anschluss

The (, or , ), also known as the (, en, Annexation of Austria), was the annexation of the Federal State of Austria into the German Reich on 13 March 1938.

The idea of an (a united Austria and Germany that would form a " Greater Germany ...

'' of Austria in 1938 and the dismemberment of Czechoslovakia (1938–1939) demonstrated the impossibility of establishing a collective security system in Europe, a policy advocated by the Soviet ministry of foreign affairs under Maxim Litvinov

Maxim Maximovich Litvinov (; born Meir Henoch Wallach; 17 July 1876 – 31 December 1951) was a Russian revolutionary and prominent Soviet statesman and diplomat.

A strong advocate of diplomatic agreements leading towards disarmament, Litvinov wa ...

. This, as well as the reluctance of the British and French governments to sign a full-scale anti-German political and military alliance with the USSR, led to the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact

The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact was a non-aggression pact between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union that enabled those powers to partition Poland between them. The pact was signed in Moscow on 23 August 1939 by German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ri ...

between the Soviet Union and Germany in late August 1939. The separate Tripartite Pact

The Tripartite Pact, also known as the Berlin Pact, was an agreement between Germany, Italy, and Japan signed in Berlin on 27 September 1940 by, respectively, Joachim von Ribbentrop, Galeazzo Ciano and Saburō Kurusu. It was a defensive milit ...

between what became the three prime Axis Powers

The Axis powers, ; it, Potenze dell'Asse ; ja, 枢軸国 ''Sūjikukoku'', group=nb originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis, was a military coalition that initiated World War II and fought against the Allies. Its principal members were ...

would not be signed until some four years after the Anti-Comintern Pact.

Forces

The war was fought between

The war was fought between Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

, its allies and Finland

Finland ( fi, Suomi ; sv, Finland ), officially the Republic of Finland (; ), is a Nordic country in Northern Europe. It shares land borders with Sweden to the northwest, Norway to the north, and Russia to the east, with the Gulf of B ...

, against the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

and its allies. The conflict began on 22 June 1941 with the Operation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa (german: link=no, Unternehmen Barbarossa; ) was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and many of its Axis allies, starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during the Second World War. The operation, code-named after ...

offensive, when Axis

An axis (plural ''axes'') is an imaginary line around which an object rotates or is symmetrical. Axis may also refer to:

Mathematics

* Axis of rotation: see rotation around a fixed axis

* Axis (mathematics), a designator for a Cartesian-coordinat ...

forces crossed the borders described in the German–Soviet Nonaggression Pact, thereby invading the Soviet Union. The war ended on 9 May 1945, when Germany's armed forces surrendered unconditionally following the Battle of Berlin

The Battle of Berlin, designated as the Berlin Strategic Offensive Operation by the Soviet Union, and also known as the Fall of Berlin, was one of the last major offensives of the European theatre of World War II.

After the Vistula– ...

(also known as the Berlin Offensive

The Battle of Berlin, designated as the Berlin Strategic Offensive Operation by the Soviet Union, and also known as the Fall of Berlin, was one of the last major offensives of the European theatre of World War II.

After the Vistula– ...

), a strategic operation executed by the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and, after ...

.

The states that provided forces and other resources for the German war effort included the Axis Powers

The Axis powers, ; it, Potenze dell'Asse ; ja, 枢軸国 ''Sūjikukoku'', group=nb originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis, was a military coalition that initiated World War II and fought against the Allies. Its principal members were ...

– primarily Romania, Hungary, Italy, pro-Nazi Slovakia, and Croatia. Anti-Soviet

Anti-Sovietism, anti-Soviet sentiment, called by Soviet authorities ''antisovetchina'' (russian: антисоветчина), refers to persons and activities actually or allegedly aimed against the Soviet Union or government power within the ...

Finland, which had fought the Winter War

The Winter War,, sv, Vinterkriget, rus, Зи́мняя война́, r=Zimnyaya voyna. The names Soviet–Finnish War 1939–1940 (russian: link=no, Сове́тско-финская война́ 1939–1940) and Soviet–Finland War 1 ...

against the Soviet Union, also joined the offensive. The ''Wehrmacht'' forces were also assisted by anti-Communist

Anti-communism is Political movement, political and Ideology, ideological opposition to communism. Organized anti-communism developed after the 1917 October Revolution in the Russian Empire, and it reached global dimensions during the Cold War, w ...

partisans in places like Western Ukraine, and the Baltic states

The Baltic states, et, Balti riigid or the Baltic countries is a geopolitical term, which currently is used to group three countries: Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. All three countries are members of NATO, the European Union, the Eurozone, ...

. Among the most prominent volunteer army formations was the Spanish Blue Division, sent by Spanish dictator Francisco Franco

Francisco Franco Bahamonde (; 4 December 1892 – 20 November 1975) was a Spanish general who led the Nationalist faction (Spanish Civil War), Nationalist forces in overthrowing the Second Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War ...

to keep his ties to the Axis intact.

The Soviet Union offered support to the anti-Axis partisans in many ''Wehrmacht''-occupied countries in Central Europe

Central Europe is an area of Europe between Western Europe and Eastern Europe, based on a common historical, social and cultural identity. The Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) between Catholicism and Protestantism significantly shaped the area' ...

, notably those in Slovakia and Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populous ...

. In addition, the Polish Armed Forces in the East

The Polish Armed Forces in the East ( pl, Polskie Siły Zbrojne na Wschodzie), also called Polish Army in the USSR, were the Polish Armed Forces, Polish military forces established in the Soviet Union during World War II.

Two armies were formed ...

, particularly the First

First or 1st is the ordinal form of the number one (#1).

First or 1st may also refer to:

*World record, specifically the first instance of a particular achievement

Arts and media Music

* 1$T, American rapper, singer-songwriter, DJ, and rec ...

and Second

The second (symbol: s) is the unit of time in the International System of Units (SI), historically defined as of a day – this factor derived from the division of the day first into 24 hours, then to 60 minutes and finally to 60 seconds ...

Polish armies, were armed and trained, and would eventually fight alongside the Red Army. The Free French

Free France (french: France Libre) was a political entity that claimed to be the legitimate government of France following the dissolution of the Third Republic. Led by French general , Free France was established as a government-in-exile ...

forces also contributed to the Red Army by the formation of the GC3 (''Groupe de Chasse 3'' or 3rd Fighter Group) unit to fulfil the commitment of Charles de Gaulle

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle (; ; (commonly abbreviated as CDG) 22 November 18909 November 1970) was a French army officer and statesman who led Free France against Nazi Germany in World War II and chaired the Provisional Government ...

, leader of the Free French, who thought that it was important for French servicemen to serve on all fronts.

The above figures includes all personnel in the German Army, i.e. active-duty Heer, Waffen SS

The (, "Armed SS") was the combat branch of the Nazi Party's ''Schutzstaffel'' (SS) organisation. Its formations included men from Nazi Germany, along with volunteers and conscripts from both occupied and unoccupied lands.

The grew from th ...

, Luftwaffe

The ''Luftwaffe'' () was the aerial-warfare branch of the German ''Wehrmacht'' before and during World War II. Germany's military air arms during World War I, the ''Luftstreitkräfte'' of the Imperial Army and the '' Marine-Fliegerabtei ...

ground forces, personnel of the naval coastal artillery and security units. In the spring of 1940, Germany had mobilised 5,500,000 men. By the time of the invasion of the Soviet Union, the Wehrmacht consisted of c. 3,800,000 men of the Heer, 1,680,000 of the Luftwaffe, 404,000 of the Kriegsmarine

The (, ) was the navy of Germany from 1935 to 1945. It superseded the Imperial German Navy of the German Empire (1871–1918) and the inter-war (1919–1935) of the Weimar Republic. The was one of three official branches, along with the a ...

, 150,000 of the Waffen-SS, and 1,200,000 of the Replacement Army (contained 450,400 active reservists, 550,000 new recruits and 204,000 in administrative services, vigiles and or in convalescence). The Wehrmacht had a total strength of 7,234,000 men by 1941. For Operation Barbarossa, Germany mobilised 3,300,000 troops of the Heer, 150,000 of the Waffen-SS and approximately 250,000 personnel of the Luftwaffe were actively earmarked.

By July 1943, the Wehrmacht numbered 6,815,000 troops. Of these, 3,900,000 were deployed in eastern Europe, 180,000 in Finland, 315,000 in Norway, 110,000 in Denmark, 1,370,000 in western Europe, 330,000 in Italy, and 610,000 in the Balkans. According to a presentation by Alfred Jodl, the Wehrmacht was up to 7,849,000 personnel in April 1944. 3,878,000 were deployed in eastern Europe, 311,000 in Norway/Denmark, 1,873,000 in western Europe, 961,000 in Italy, and 826,000 in the Balkans. About 15–20% of total German strength were foreign troops (from allied countries or conquered territories). The German high water mark was just before the

By July 1943, the Wehrmacht numbered 6,815,000 troops. Of these, 3,900,000 were deployed in eastern Europe, 180,000 in Finland, 315,000 in Norway, 110,000 in Denmark, 1,370,000 in western Europe, 330,000 in Italy, and 610,000 in the Balkans. According to a presentation by Alfred Jodl, the Wehrmacht was up to 7,849,000 personnel in April 1944. 3,878,000 were deployed in eastern Europe, 311,000 in Norway/Denmark, 1,873,000 in western Europe, 961,000 in Italy, and 826,000 in the Balkans. About 15–20% of total German strength were foreign troops (from allied countries or conquered territories). The German high water mark was just before the Battle of Kursk

The Battle of Kursk was a major World War II Eastern Front engagement between the forces of Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union near Kursk in the southwestern USSR during late summer 1943; it ultimately became the largest tank battle in history. ...

, in early July 1943: 3,403,000 German troops and 650,000 Finnish, Hungarian, Romanian and other countries' troops.

For nearly two years the border was quiet while Germany conquered Denmark, Norway, France, the Low Countries, and the Balkans

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

. Hitler had always intended to renege on his pact with the Soviet Union, eventually making the decision to invade in the spring of 1941.

Some historians say Stalin was fearful of war with Germany, or just did not expect Germany to start a two-front war

According to military terminology, a two-front war occurs when opposing forces encounter on two geographically separate fronts. The forces of two or more allied parties usually simultaneously engage an opponent in order to increase their chance ...

, and was reluctant to do anything to provoke Hitler. Others say that Stalin was eager for Germany to be at war with capitalist countries. Another viewpoint is that Stalin expected war in 1942 (the time when all his preparations would be complete) and stubbornly refused to believe it would come early.

British historians Alan S. Milward and M. Medlicott show that Nazi Germany—unlike Imperial Germany—was prepared for only a short-term war (Blitzkrieg). According to Edward Ericson, although Germany's own resources were sufficient for the victories in the West in 1940, massive Soviet shipments obtained during a short period of Nazi–Soviet economic collaboration were critical for Germany to launch Operation Barbarossa.

Germany had been assembling very large numbers of troops in eastern Poland and making repeated

Germany had been assembling very large numbers of troops in eastern Poland and making repeated reconnaissance

In military operations, reconnaissance or scouting is the exploration of an area by military forces to obtain information about enemy forces, terrain, and other activities.

Examples of reconnaissance include patrolling by troops (skirmisher ...

flights over the border; the Soviet Union responded by assembling its divisions on its western border, although the Soviet mobilisation was slower than Germany's due to the country's less dense road network. As in the Sino-Soviet conflict on the Chinese Eastern Railway

The Chinese Eastern Railway or CER (, russian: Китайско-Восточная железная дорога, or , ''Kitaysko-Vostochnaya Zheleznaya Doroga'' or ''KVZhD''), is the historical name for a railway system in Northeast China (als ...

or Soviet–Japanese border conflicts

The Soviet–Japanese border conflicts, also known as the Soviet-Japanese Border War or the First Soviet-Japanese War,was a series of minor and major conflicts fought between the Soviet Union (led by Joseph Stalin), Mongolia (led by Khorloo ...

, Soviet troops on the western border received a directive, signed by Marshal

Marshal is a term used in several official titles in various branches of society. As marshals became trusted members of the courts of Medieval Europe, the title grew in reputation. During the last few centuries, it has been used for elevated o ...

Semyon Timoshenko

Semyon Konstantinovich Timoshenko (russian: link=no, Семён Константи́нович Тимоше́нко, ''Semyon Konstantinovich Timoshenko''; uk, Семе́н Костянти́нович Тимоше́нко, ''Semen Kostiantyno ...

and General of the Army Georgy Zhukov

Georgy Konstantinovich Zhukov ( rus, Георгий Константинович Жуков, p=ɡʲɪˈorɡʲɪj kənstɐnʲˈtʲinəvʲɪtɕ ˈʐukəf, a=Ru-Георгий_Константинович_Жуков.ogg; 1 December 1896 – ...

, that ordered (as demanded by Stalin): "do not answer to any provocations" and "do not undertake any (offensive) actions without specific orders" – which meant that Soviet troops could open fire only on their soil and forbade counter-attack on German soil. The German invasion therefore caught the Soviet military and civilian leadership largely by surprise.